With my brother

My younger brother Merrill has always been the cautious one. Growing up north of Boston, I took on my parents in any argument; he stayed silent. I slalomed down ski slopes, sometimes crashing into trees; he executed a perfect, steady snowplow downhill. I became a journalist, venturing into war zones; he became a lawyer, specialising in intellectual property and contracts. Before he came back to South Africa two years ago, his only visit since my 1990 wedding, the only wildlife he’d seen were deer and squirrels in the New England woods or those caged in a zoo. Our trip to Addo – though a rerun for me – for him was a revelation.

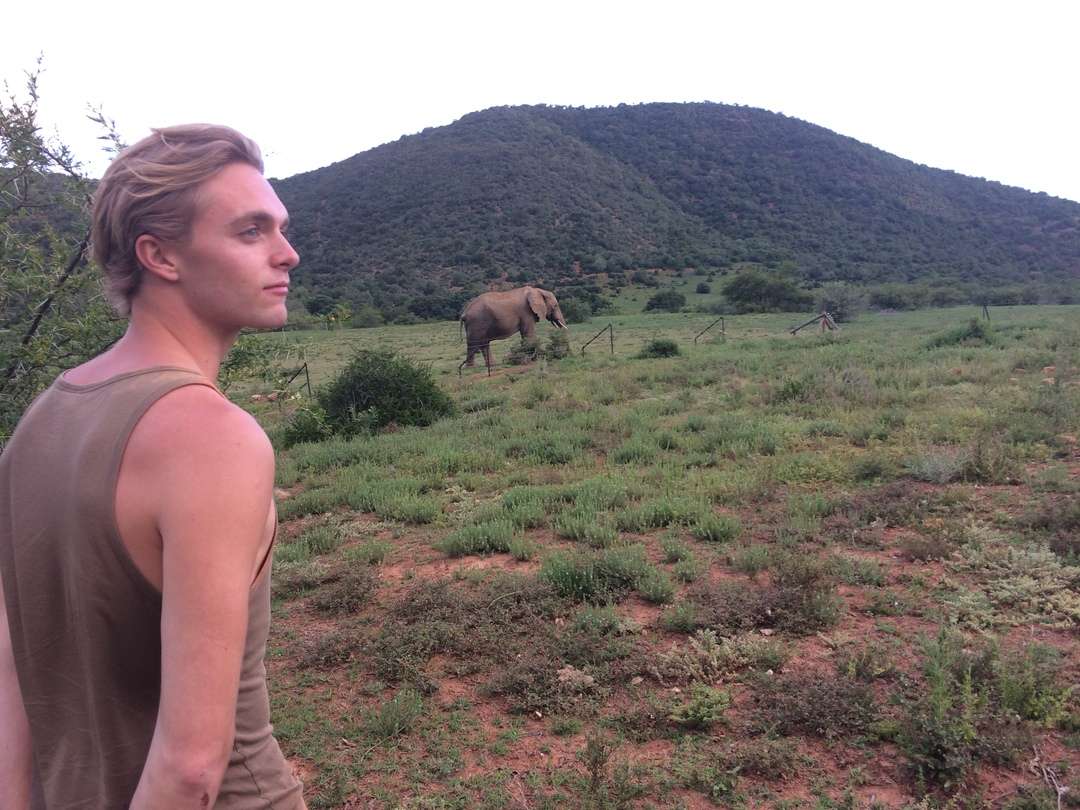

My brother Merrill, thrilled to be setting off on his first game drive ever, Addo

At first the vervet monkeys hanging around our safari tent alarmed him, but they quickly became part of landscape; you wise up fast when they’re trying to snatch just about everything. Eland and other antelope at a waterhole fronting our tents distracted us; soon Merrill was an eager lookout – and a rabid photographer, snapping away at anything that moved.

His first game drive was relatively uneventful: a few elephants, far away; the ubiquitous impalas and kudus; zebra upon zebra herd. But Merrill was delighted, even with the vehicle itself. Nothing matches the Zen ‘beginner’s mind’ for amazement.

Merrill was surprisingly calm as this enormous bull approached and passed us

Our last day brought the most surprises: first a guided horseback ride, where Merrill – on a horse before only a handful of times – gamely cantered along with the rest of us, loving every minute. That afternoon we had our most thrilling – and blood-pumping – elephant encounter. We rounded a corner and saw an SUV stopped up ahead, and the reason why: a giant bull with tusks like sabres commanded the road, walking towards them, and us. We pulled over to the left as far as possible, almost into the bush, to let him pass. Stopped, but kept the engine running. Lumbering along, he dwarfed the SUV, which he passed slowly, coming our way. For a minute or so he was headed straight towards us, ears flapping slightly. I thought my brother would panic. But dead silent, he filmed the elephant’s approach on his phone; I snapped a photo of him as he passed on the driver’s side. I could have touched him if I leaned out the window. When he was behind us, we burst into laughter and exclamation; the thrill hasn’t left us.

Not a rider, my brother embraced the Addo experience wholeheartedly

I’ve looked at Merrill differently since our little safari; he’s braver than I remembered. After years of being apart, that shared experience in the African bush brought our hearts back together.

With my mother

An African safari – actually a pair of them, back to back – is not something I associated with Mom, Barbara Jacqueline Bell Soule Baumann Shipley, whose relatives sailed on the Mayflower and are buried in Boston Common. But when Jack, her second husband and my stepfather, died after a grim demise from Alzheimer’s 28 years ago, I invited her to Cape Town, then onwards to the Okavango and Kalahari.

It was rough, a far cry from the comfort she was used to in her travels. Run by an overland tour operator, each safari was two weeks of driving into the wilderness with a not totally compatible bunch of strangers. Definitely not the aristocratic ladies Mom played tennis with every week at the club.

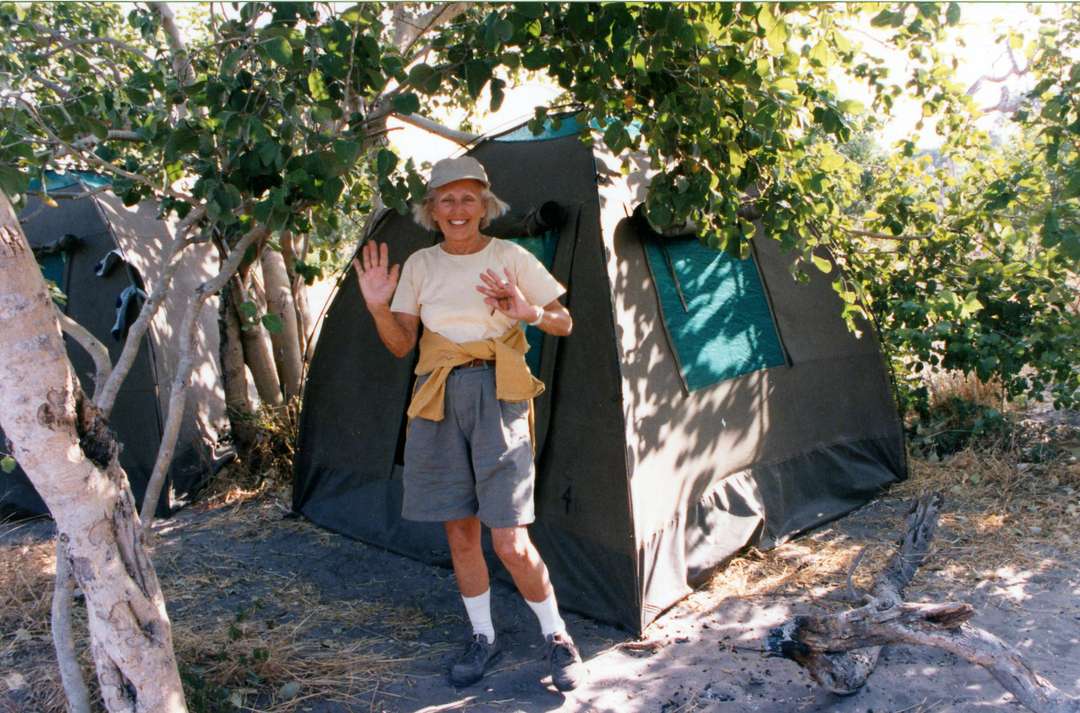

My mother - a magnet for wildlife on safaris that saved her

In the Okavango, I shared a tent with my husband Hannes, which left Mom on her own. She charmed one particular assistant guide, always ready to help her put up her tent, and to answer her many questions. Like this one, asked one morning as we packed up camp on a small, palm-covered island: ‘What was that noise I heard all night? It sounded like a lawn mower!’ The guide checked around her fallen tent and told her: at least one hippo had munched his way around her as she slept. Or tried to sleep. The next night an elephant tearing branches off the tree overhanging her tent kept her awake. But Mom figured that one out.

Hannes skipped the second safari, so Mom and I shared a tent, and much else. Driving, driving, driving with the others, often in silence, in the dry heat across the semi-desert, to the Central Kalahari – stopping occasionally at a Bushman settlement but mostly moving through what looked like a vast emptiness. A gemsbok here and there; the lovely trees of Mabuasehube, strangely like a manicured English park; the moonscape of the Makgadikgadi Pans. Much time spent going inward, reflecting, the growing bonds unspoken, old bonds renewed.

After a month of travelling, we returned to Cape Town. Mom’s spirit seemed lighter. I still worried about her, sending her off solo again. ‘That was the best trip I’ve ever done’, she told me at the airport, about to fly back to America. Liberated.

She died seven years later, 21 years ago – but our safaris together seem like yesterday.

Written and photographed by Melissa Siebert